COVER STORY

My father’s father’s father was a romantic Turkish politician who ran a small but distinguished conservative magazine, and whose career ended in a series of judgments that were romantic and certainly conservative, but unwise and sometimes reckless.

Most reckless of all was when my ancestor took it upon himself, as interior minister in the government of the last sultan, to sign the arrest warrant for Ataturk, now acknowledged to be the father of modern Turkey, and whose visage adorns almost every municipal building in the country. A short while later, my great-grandfather was having a shave in a place called Izmit when he was beaten to death and stuck in a tree. That is why my paternal grandfather, who was born Osman Ali, arrived in this country in search of what would now be called asylum.

I say all this to demonstrate that although I am of course British, and have far more English than Turkish blood, I have a predisposition to be sympathetic to those who have come to this country, in fear of their lives or not, with the intention of making a new start.

The reason we worry about the scale and pace of immigration today is that, bluntly, the present influx does not seem to be assimilating in quite the same way as their predecessors did. According to Andrew Green of Migrationwatch, the net inflow of immigrants to Britain is now about 170,000 per year, a figure which takes no account of failed asylum-seekers who do not leave the country, and other illegals. We are apparently expecting an extra two million non-EU immigrants per decade and, pro-immigrant though I am, that strikes me as a legitimate subject for political discussion. Never one for being outflanked on the Right, David Blunkett has already warned that people feel swamped. More significantly, it now appears to be acceptable, in left-wing circles, to call attention to the threat posed by immigration to the British way of life.

A couple of Harvard economists, Messrs Alesina and Glaeser, have produced a fascinating explanation for the different willingness, in Europe and America, to take money from the rich and spend it on the poor. Government spending in America is about 30 per cent of GDP, and in Europe it is about 45 per cent of GDP, and one important explanation for the difference, say the economists, is race. It seems that people are more likely to support welfare if they live close to recipients of their own race, and they are more likely to be antipathetic to it if they live close to citizens of another race. This insight has been seized on by the Left, and provoked an anguished article by David Goodhart in Prospect, called ‘Too Diverse?’, in which he says that if we have a society that is too diverse, too multicultural, too Balkanised into immigrant groups, then we will lose that sense of reciprocity and mutuality and community that we need to maintain people’s commitment to the welfare state. So at the beginning of the 21st century, amid general paranoia about globalisation and immigration, nationalism is being invoked by the Left for the salvation of socialism in one country. Now you or I might think there were plenty of other good reasons for wanting to preserve a spirit of reciprocity and community, beyond the Goodhartian ambition of protecting the pristine integrity of our 1948 welfare settlement. But there is one underlying assumption in the discourse of Goodhart, Blunkett and Green, and that is the reality of racism. It now seems to be accepted on the Left — when it was never accepted before — that racism is endemic in the species.

I don’t want my taxes wasted on scroungers of any colour; but it seems to be common ground that people’s resentment is accentuated if they feel the money is going on foreigners, and particularly on foreigners of a different colour. That strikes me as being sad but probably unavoidable; and in that sense racism is like sewage: something that a civilised society will manage and channel. The question is how.

The most obvious answer is to prevent huge numbers of unassimilated people arriving in such a way as to perturb the indigenous people; and if you are in favour of immigration, which I am, then you should be in favour of people who come here to work, and you should not so disastrously mismanage the asylum system that hundreds of thousands of illegals are left in limbo, technically forbidden to be economically active and a continual irritation, therefore, to the taxpayer. But given the scale and pace of the immigration already under way, that is not enough; and here we come to the second and most amazing volte-face by the Left.

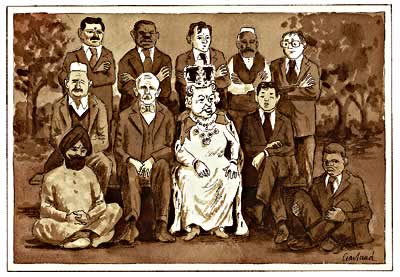

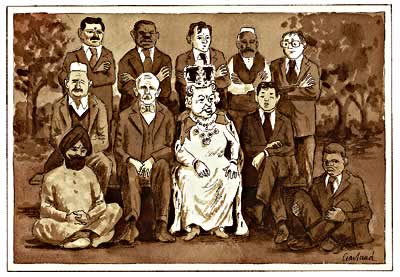

Almost seven years after New Labour came to power, vowing to do away with Old Britain, they have rediscovered the vitality of old symbols in a way that is hilarious and also rather moving. On 26 February this year, members of the Hatterjee family became British citizens in a ceremony described by Ferdinand Mount in a recent issue of The Spectator. They were serenaded by the national anthem and they shook hands with the Prince of Wales. And all these people, thousands a month, are not only swearing or affirming their allegiance to the Queen, her heirs and successors. There is now a new pledge, which one might call the Tipton Taleban clause. ‘I will give my loyalty to the UK, and respect its rights and freedoms,’ says the pledge. ‘I will uphold its democratic values. I will observe its laws faithfully and fulfil my duties and obligations as a British citizen.’

Consider the astonishing implications of those words — astonishing, that is, for this country to demand. ‘I will give my loyalty to the UK.’ Ten years ago Norman Tebbit suggested that immigrants should pass the cricket test: that third- or fourth-generation UK citizens, sitting in the crowd at Lord’s, should on the whole requite the benefits they have received in this country by cheering for England. At the time this feline observation was denounced — across the political spectrum — as quite irresponsibly provocative. And now a Labour government explicitly demands loyalty to the UK. If you accept, as seems reasonable, that loyalty to the UK is logically indivisible from sporting allegiance, then Norman Tebbit’s cricket test has been given ceremonial form by David Blunkett. Early reports suggest that the naturalised immigrants love these ceremonies; they love the Union flag there — the very flag that is banned from the lockers in the workplace on the grounds that it is intimidatingly racist — and the government loves them, too. That is because there has long been a recognition that Britain will not work if it is just what Philip Bobbitt called a market state.

You could in theory construct a polity in which no one had any particular romantic attachment to the nation itself; and we could all live wherever we happened to be in the same spirit of emotional detachment, paying our taxes, and in return receiving certain services and protections. Of course it would be a rather dismal sort of place; and it would also be impractical. Because the key feature of nation states is that they do demand of their citizens the willingness to make sacrifices for the general good, and on the whole people will make those sacrifices only if they feel a basic loyalty to the nation. It is as if the government is appalled at the fissiparous effect of multiculturalism, and is suddenly reaching for the glue.

That is the meaning of these citizenship ceremonies. Left-wingers have finally grasped that if this country is to succeed, if it is to be cohesive, we must have a basic and shared understanding of what it means to be British. It would be fair to say that Labour has ended up, in 2004, with a rather different interpretation of being British from that with which it began in 1997.

For much of its seven years in power, Labour has mounted an assault on what it conceives of as the institutions of Old Britain. You remember Cool Britannia, and the moronic and ahistorical Dome, and Cherie’s refusal to curtsy, and Bob Ayling’s preposterous and commercially disastrous removal of the flag from the tailfins of BA jets. It was just the beginning of a New Labour project to reconfigure what it meant to be British, and the agenda was spelt out by Gordon Brown in a speech in April 1999, only four years ago. ‘Old Britain is going,’ announced Gordon, who still likes to give two fingers to tradition by turning up in a suit for the Lord Mayor’s banquet. ‘The old order of unreformed institutions is passing into history.’

It was pretty clear that by these institutions he meant the union between England and Scotland, the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty and, sotto voce, the monarchy. He pointed with excitement to a poll showing that the public didn’t think much of the House of Commons as an emblem of Britishness. It was old-fashioned to think that power had to be centred on London, he said, and extolled the genius and dynamism of the coming regional governments. He cited Professor Linda Colley, to the effect that the institutions of a united Britain were really the creation of empire and external peril; and those things having been removed, the tired old crenellated institutions of Britain could be broken up and reformed, and sovereignty could be pooled with Europe. No, he said, what really united the nation was not Parliament but the NHS, chosen by 71 per cent as the thing most representative of Britain.

One can see why this might be appealing to a Labour politician who has so vastly expanded the public sector — though not necessarily front-line staff — and entrenched the position of the NHS as the biggest state employer this side of the Urals. But when you are stuck in some foreign hell-hole, and thinking green thoughts of home, do you necessarily think of the NHS, with all its beauties and advantages? Do you pine, like Rupert Brooke in the first world war, and wish you were in some NHS ward? I’m not sure.

And if it wasn’t the NHS that united the nation, said Gordon Brown, it was the BBC; and again one can see why the idea of 20,000 taxpayer-funded journalists of preponderantly leftish views might have seemed congenial to Gordon then, if not now. Then he told us that being British meant that everyone who can work has the right and responsibility to do so. This strikes me as a little glib, to say the least. There is nothing particularly unBritish about a wife who stays at home to look after the children, or stays at home to watch the television, or indeed a belted earl who has never done a day’s work in his life. But these things, at any rate, were the aspects of Britishness that Labour chose to extol: the NHS, the BBC, and the Gordon Brownian obsession with work; and the other tired old symbols of Britishness they set about to deprecate or destroy.

The Crown was removed from the Treasury letterhead. I remember being amazed, sitting on some Police Bill, when we just nodded through a clause changing the oath of loyalty sworn by police constables so as to remove a specific reference to the Queen. I went into the Lobby, found Chris Moncrieff of the Press Association, issued a torrential statement of denunciation, and heard no more about it.

The government will shortly agree a new constitution for this country, hammered out in unintelligible negotiations with other European countries, and will not even give us a vote on it. The absurdity of regional government continues, in the sense that gravel pits can be dug or houses built in south Oxfordshire, on the say-so of some Guildford bureaucrat. We now have a devolved system of government in which measures can be imposed on England by Scottish MPs, when I as an English MP have no say over those questions in Scotland and — the final absurdity — they, sitting for Scottish seats, have no say themselves. The hereditaries have been banned, or will be shortly; and still the Kulturkampf goes on.

If you are staying in the Marriott Kampala and you meet someone in the Windsor Suite, where the hotel managers will have gone to great trouble to find some British-style prints to put on the walls, what will you see? It is a dime to a dollar that those pictures — intended by the globalised hotel business to connote Britain — will show scenes of fox-hunting, a sport that is to be banned by Labour not for reasons of cruelty, but because of chippiness and class war, and because fox-hunting is so deeply redolent of Old Britain.

Only last month the government announced, for no reason at all other than a vague teenage republicanism, that they were going to remove the reference to the Crown from the Crown Prosecution Service. And yet this is the very government which now asks newcomers not just to swear an oath of loyalty to the Crown, but also to the United Kingdom. This resentful adolescent Labour government, after six years of spite and vindictiveness, has just installed a ceremony in which the Union flag is prominently displayed and everyone sings ‘God Save the Queen’. What is going on? The answer is that we are witnessing a screeching and undignified U-turn, at least by one part of the government.

When immigrants come here, they instantly see the point of symbols like flags, and anthems, and the Queen, whose DNA incarnates British history in a way that people understand all over the world. For 20 years the Labour party was completely wrong in the main economic arguments. It is now dawning on them — not fast enough — that they may also have been wrong in the cultural arguments, and that their adherence to the doctrine of multiculturalism has been a mistake, because it produces a segregated market state where people insist on their rights, but have no sense of common loyalty or purpose. If you want to engender that loyalty, it is no use appealing to the NHS, or the BBC, or our common desire to work, as Gordon Brown suggests. You have to go back to the things that really resonate in people’s hearts; and while Conservatives have no monopoly on those institutions, it is certainly a conservative insight that they should not be lightly cast aside.

This is an abridged version of the Keith Joseph Memorial Lecture delivered to the Centre for Policy Studies on 25 March 2004.

© 2004 The Spectator.co.uk